Abstractions are there to hide irrelevant things and focus only on the essential details. Although it may seem scary sometimes, it is the best tool to manage complexity.

If you ask mathematicians to define what mathematics is about, you'll probably get different answers. My definition would be that it is the science of abstracting things away until only the core is left, providing the ultimate framework for reasoning about anything.

Have you ever thought about what probability really is? You have already used it to reason about data, do statistical analysis, or even build algorithms to do the reasoning for you by statistical learning. In this post, we go deep into the rabbit hole and explore the theory of probability with a magnifying glass.

Prerequisites

To follow through, you don't need any advanced mathematics. I am focusing on explaining everything from the ground up. However, it is beneficial if you know the following:

- Sets and set operations such as union, intersection, and difference.

- Limits and some basic calculus.

Sets and measures

Probability can be heuristically thought of as a function measuring the likelihood of an event happening. Mathematically speaking, it is not yet clear at all what events and measures are. Before we can properly discuss probability, we need to make a solid footing first. So, let's start with events.

Events

What is the probability that I roll an odd number with a dice?

This simple question comes into our mind as an example when talking about probabilities. In this simple question, the event is rolling an odd number. To model this mathematically, we use sets. The "universe" - the base set containing the outcomes of this experiment - is simply and an event is a subset of . Here, rolling an odd number corresponds to the subset .

So, to define probability, you need an underlying set and a collection of its subsets , which we will call events. However, cannot just be any collection of subsets. There are three conditions that must be met.

- is an event.

- If is an event, then its complement is also an event. That is, an event not happening is another event as well.

- The union of events is an event as well. In other words, is closed to the union.

If these are satisfied, is called a σ-algebra. In proper mathematical terminology:

In our case, we have

A more interesting case arises when is the set of real numbers. Later we'll see that if all subsets of the real numbers are considered events, then strange things can happen.

Describing σ-algebras

These event spaces, which we define with σ-algebras, can be hard to describe. One can instantly see that to have a meaningful event space on a nontrivial base set , we should have an infinite number of events. For instance, we are shooting bullets on a board and calculating the probability of hitting a specific region. In these cases, it is enough to specify some subsets and take the smallest σ-algebra containing these.

Let's suppose we are shooting at a rectangular board. If we say that our event space is the smallest σ-algebra containing all rectangle subsets of the board, we

- have a straightforward description of the σ-algebra,

- containing all kinds of shapes. (Since σ-algebras are closed under union.)

A lot of sets can be described as the infinite union of rectangles, as we see below.

We call the set of rectangles inside the board the generating set, while the smallest σ-algebra is the generated σ-algebra.

You can think about this generating process as taking all elements of your generating set and taking unions and complements in all the possible ways.

Now that we have a mathematical framework to work with events, we shall focus on measures.

Measures

Although intuitively measuring something is clear, this is a challenging thing to formalize properly. A measure is a function, mapping sets to numbers. To consider a simple example, measuring the volume of a three-dimensional object seems simple enough, but even here, we have serious problems. Can you think of an object in the space for which you cannot measure the area?

Probably you can't right away, but this is not the case. We can show that if every subset of the space has a well-defined volume, you can take a sphere of unit volume, cut it up into several pieces, and put together two spheres of unit volume.

This is called the Banach-Tarski paradox. Since you cannot do this, it follows that you cannot measure the volume of every subset in space.

But in this case, what are measures anyway? We only have three requirements:

- the measure of any set should always be positive,

- the measure of the empty set should be zero,

- and if you sum up the measures of disjoint sets, you get the measure of their union.

To define them properly, we need a base set and a σ-algebra of subsets. The function

is a measure if

Property 3. is called σ-additivity. If we only have a finite number of sets, we will simply refer to it as the additivity of the measure.

This definition is simply the abstraction of the volume measure. It might seem strange, but these three properties are all that matters. Everything else follows from them. For instance, we have

which follows from the fact that and are disjoint, and their union is .

Another important property is the continuity of measures. This says that

Describing measures

As we have seen for σ-algebras, you only have to give a generating set instead of a full σ-algebra. This is very useful for us when working with measures. Although measures are defined on σ-algebras, it is enough to define them on a generating subset. Because of the σ-additivity, it determines the measure on every element of the σ-algebra.

The definition of probability

Now everything is set to define probability mathematically. A probability space is defined by the tuple , where is the base set, is a σ-algebra of its subsets, and is a measure such that .

So, probability is strongly related to quantities like area and volume. Area, volume, and probability are all measures in their own spaces. However, this is quite an abstract concept, so let's give a few examples.

Coin tossing

The event of coin tossing describes the simplest probability space. Say if we code heads with 0 and tails with 1, we have

Due to the properties of the σ-algebra and the measure, you only need to define the probability for the event (heads) and the event (tails), this determines the probability measure entirely.

Random numbers

A more interesting example is connected to random number generation. If you are familiar with Python, you have probably used the random.random() function, which gives you a random number between 0 and 1. Although this might seem mysterious, it is pretty simple to describe it with a probability space.

Again, notice that it is enough to give the probabilities on the elements of the generating set. For example, we have

To see a more complicated example, what is ? How can we calculate the probability of picking 0.5? (Or any other number between zero and one.) For this, we need to rely on the properties of measures. We have

which holds for all . Here, we have used the additivity of the probability measure. Thus, it follows that

Again, since it holds for all , this means that the probability is smaller than any positive real number, so it must be zero.

A similar argument follows for any . It might be surprising to see that picking a particular number has zero probability. So, after you have generated the random number and observed the result, know that it had exactly 0 probability of happening. Yet, you still have the result right in front of you. So, events with zero probability can happen.

Distributions and densities

We have gone a long way. Still, working with measures and σ-algebras is not very convenient from a practical standpoint. Fortunately, this is not the only way of working with probabilities.

For simplicity, let's suppose that our base set is the set of real numbers. Specifically, we have the probability space , where

and is any probability measure on this space. We have seen before that the probabilities of the events determine the probability for the rest of the events in the event space. However, we can compress this information even further. The function

contains all information we have to know about the probability measure. Think about it: we have

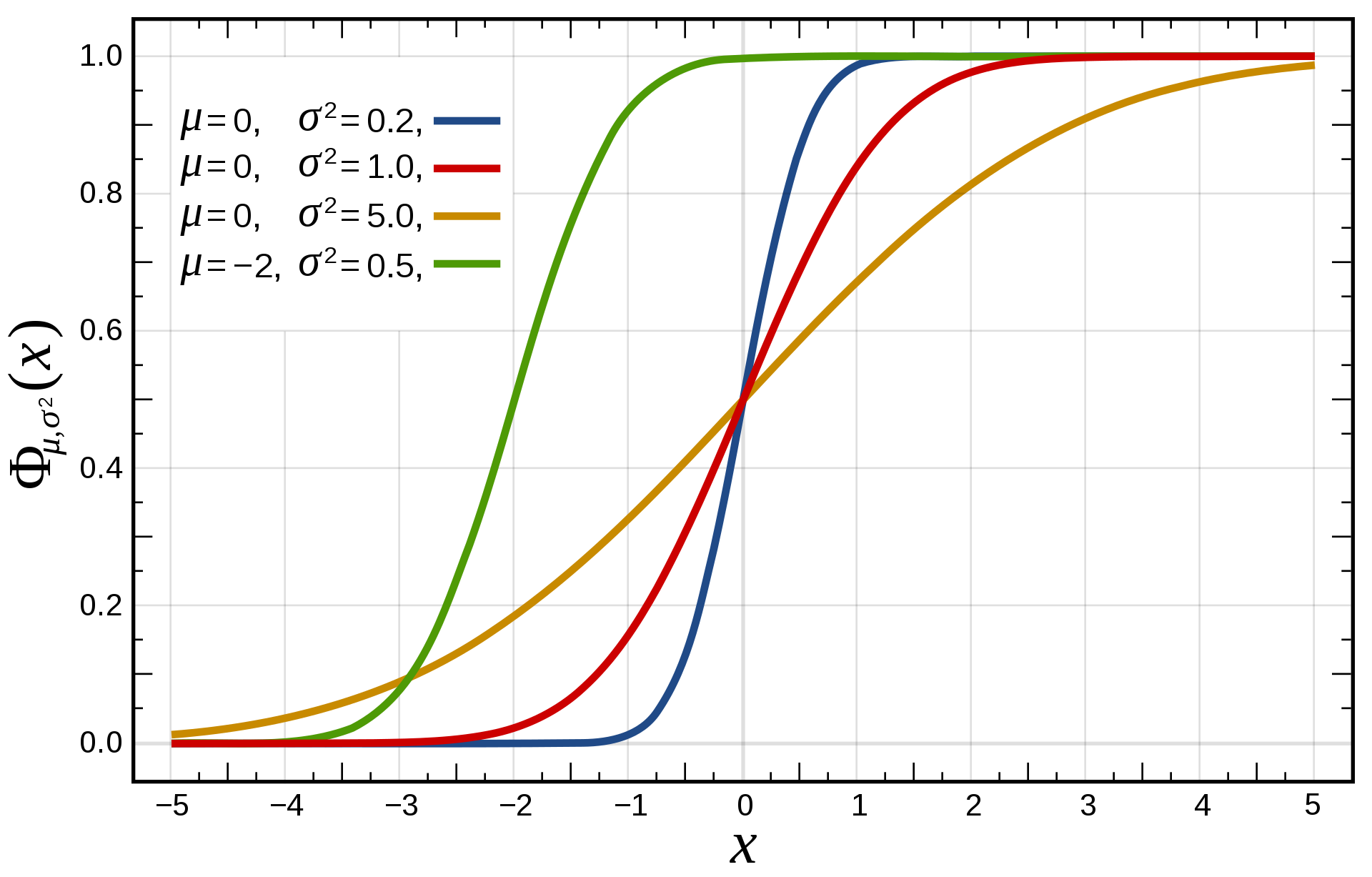

for all and . This is called the distribution function of . For all probability measures, the distribution function satisfies the following properties:

(The 4th one is called left continuity. Don't stress if you are not familiar with the definition of continuity. It is not essential now.)

Again, if this is too abstract, let's consider an example. For the previous example of random number generation, we have

This is called the uniform distribution on .

To summarize, if you give me a probability measure, I'll give you a distribution function describing the probability measure. However, this is not the best about distribution functions. From a mathematical perspective, it is also true that if you give a function satisfying the properties 1)–4) above, I can construct a probability measure from it. Moreover, if two distribution functions are equal everywhere, then their corresponding probability measures are also identical. So, from a mathematical perspective, distribution functions and probability measures are equivalent. This is extremely useful for us.

Density functions

As we have seen, a distribution function takes all information from a probability measure and essentially compresses it. It is a great tool, but sometimes it is not convenient. For instance, calculating expected values is hard when we only have a distribution function. (Don't worry if you don't know what is expected value, we won't use it right now.)

For many practical purposes, we describe probability measures with density functions. A function is the density function for the probability measure P if

holds for all in the σ-algebra . That is, heuristically, the probability for a given set is determined by the area under the curve of . This definition might seem simple, but there are many details hidden here, which I won't go into. For instance, it is not trivial how to integrate a function over an arbitrary set .

You are probably familiar with the famous Newton-Leibniz rule from calculus. Here, this says

which implies that if the distribution function is differentiable, its derivative is the density function.

There are certain probability distributions for which only the density function is known in closed form. (Having a closed form means expressing it with a finite number of standard operations and elementary functions.) One of the most famous distributions is like this: the Gaussian. It is defined by

where and are its parameters.

However surprising it may seem, we can't express the distribution function of the Gaussian in closed form. It is not that mathematicians just haven't figured out. It is proven to be impossible. (Proving that something is impossible to do in mathematics is usually extremely hard.)

Where to go from here?

What we have seen so far is only the tip of the iceberg. (Come to think of it, this can be said at the end of every discussion about mathematics.) Here, we have only defined what is probability in a mathematically (semi-)precise way.

The truly interesting stuff, like machine learning, is still before us.

If you would like to start, I wrote a detailed article on how we can formulate machine learning in terms of probability theory. Check it out!

Tivadar Danka

Tivadar Danka